Yasuni, a tale of two worlds [by Karla Gachet & Ivan Kashinsky]

When we were commissioned to do the story of the Waoranis in the Yasuni National Park, we did not imagine how difficult it would be. We had a month to investigate, make contacts and get all the permits. The challenge was to show the reality of these communities and staying away from stereotypes and the romanticism that surround many of the photographs of communities living in the Amazon rainforest. This was the first hurdle. The Waoranis (Waos) have been portrayed for decades and are accustomed to journalists and photographers entering their world, asking them to undress and then leaving as fast as they came. They have also learned, in the fifty years they have been in contact with our world, that nothing is free in this life. For them everything is a negotiation. In one community we were asked to pay $ 400 for overnight camping. Another time, our guide gave away all of our food to the people in the communities and we were left with no supplies in the middle of the jungle. The thing is, private property has never been a part of their life. We invented this concept.

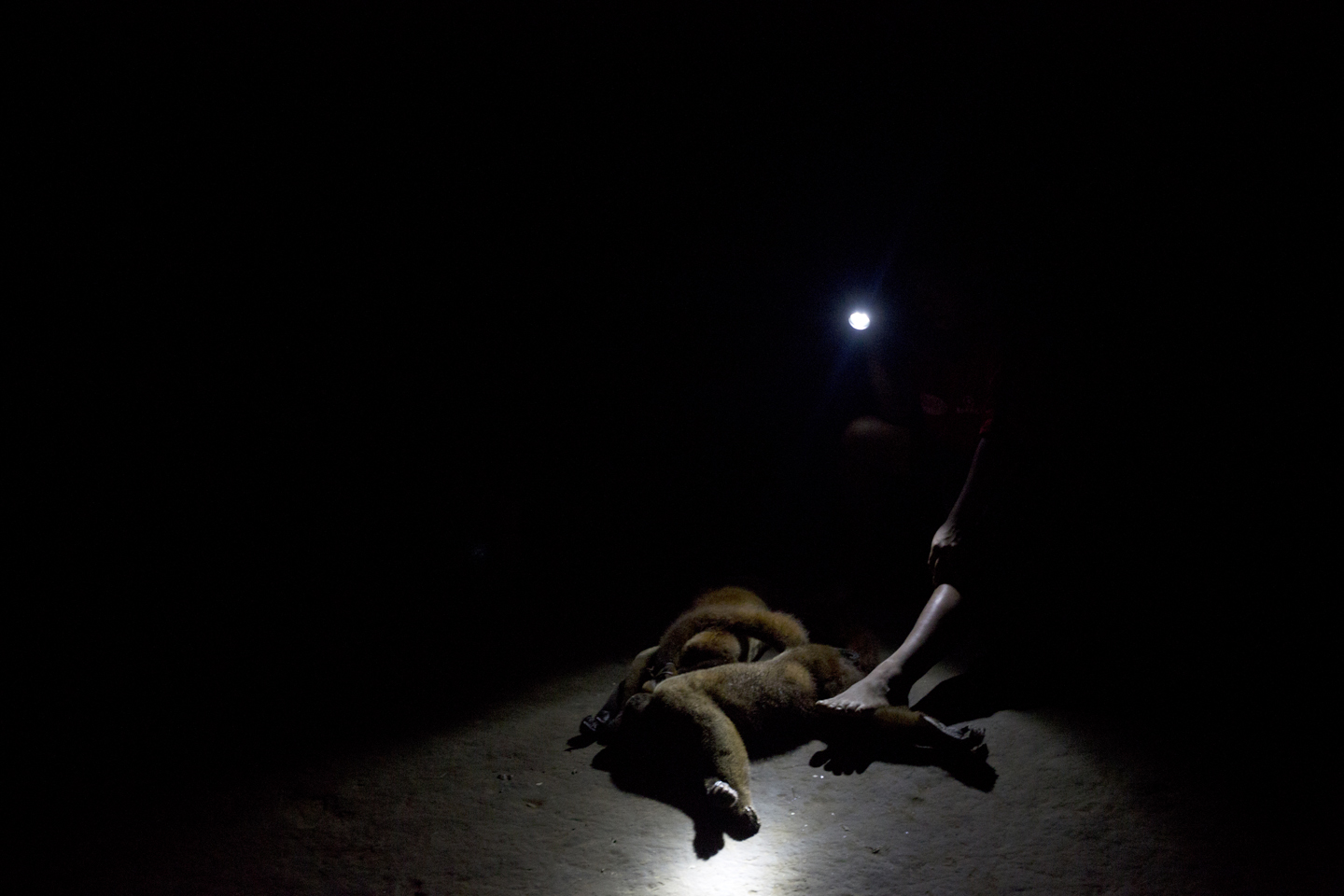

But the most interesting part was to enter their world, so distant from ours, so different from what one can imagine. Wao adults, especially grandparents, remember when they lived in voluntary isolation with their extended families. The homicide rate was 70%. This culture of violence is not something that can be erased that easily. This can be seen in the massacres that have occurred between the contacted and un-contacted or against loggers today. They were not agrarian. They were hunters and gatherers in a forest that always provided for them. When animals were scarce, they simply moved elsewhere. They still keep a very close relationship with their forest. Venturing with them, when they hunt, is a foreign experience, so different from the supermarket. They know when a branch is broken or when an animal has just passed. They hear everything around them and can imitate the sound of any animal.

One night we witnessed the magic they still live in. A man slipped into a trance and the spirit of a jaguar was speaking through him. The community talked to him through his wife. They asked where there would be good hunting the next day. A man with back pain approached the jaguar so he would blow on his back and release the pain. All this in absolute darkness, surrounded only by a symphony of insects and the hidden eyes of their cousins, the ones who still live in voluntary isolation. That night the Waos tried to make contact. A group of men walked into the jungle to yell, “Do not be afraid, we are family.” That night "someone" stole burning wood from an old woman’s campfire. She said it was a normal occurrence, " they always pass through here," she said without changing her tone of voice.

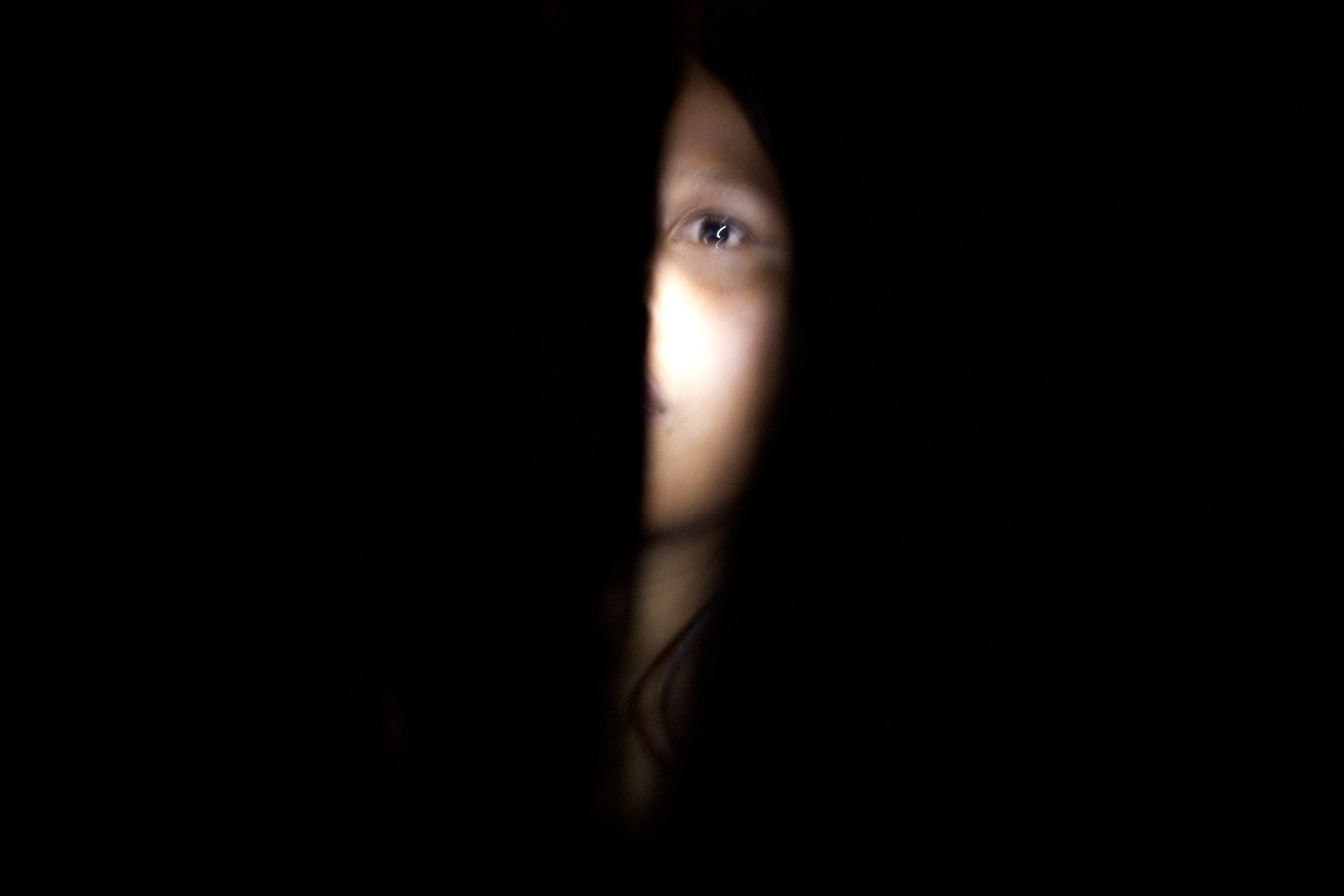

Just fifty years ago they were the ones in voluntary isolation. Contact with our civilization brought them diseases, evangelization, shotguns, lots of money and an imbalance in their lifestyle. The first baskets thrown by the evangelicals from military helicopters had salt and sugar. They thought this was what they needed. The Waorani, after trying the substances, concluded they were being poisoned. Today, a conversation with a Wao still starts with how many brothers you have and how many are in your family. The basics. That’s what seems most important to them. Although they receive money and have become part of our monetary system of slavery, they are very bad at managing it and pay inflated amounts for a watch or a piece of land and have been victims of many scams. But when they return to their jungle, money is worthless and they are back in control. And as with many other cultures, women lead their families and many NGOs prefer to work with them in community development projects. Women were our gateway to many situations. For Wao women things are always more simple and clear. So when they marched to the capital to protest the government's decision to exploit the ITT, we knew it was a different kind of protest. The protesters were mothers, sisters and daughters who were really worried about the future of their families and their land.

After a month of navigating the rivers of the Yasuní, walking through the communities, and getting to know their characters, it still didn’t feel like enough to have a complete understanding of the situation. We just documented what we saw and tried to decipher a complex situation. There are many thoughts about who is right or wrong, but in the end everything is subjective. What became clear is that the government has ignored this group since contact was first made. They let oil companies control basic needs such as health and education. The same people who have polluted the rivers give classes to the indigenous on how to care for their rainforest. The ironies are chilling. The Waorani live between two different worlds. No one is looking out for their interests in either one. Just the fact that these ancient cultures exist, should be reason enough to safeguard their welfare and their environment. But their territory has become no man's land.